I have known for some time previous Diego Barboza’s nudes, so that the perspective of being able to appreciate a new set, dedicated to a monothematic exhibition, it could only please me because the expectations were high, both from the artist as from the public , habituated to the excellence of his still lives or belongings and his characters. Post historical- as the Hipoinfantes. And with the nude, Barboza is doubly challenging because he chooses his models according to his way of painting and these are no longer teenagers or young beautiful women, of perky breasts and with that "smooth flesh that incites a bite", -according to Baudelaire’s verse- but women of flesh hit by time and life, distorted and deformed again by the art of Barboza. As in a Boucher’s nude the spectator could doubly indulge, in the good painting and the beauty of the model, this way Barboza banishes the second option so that only the first reading is allowed: the beauty of painting itself and by itself.

I would have named this exhibition of oil paintings and pastels The story of Venus and for the following reason. According to the myth on the origin of Aphrodite, it is Cronos, the god of time, who severs, in front of Gaia, Ouranos’ testicles, they fall into the sea and from the union of the semen with the water the goddess is born. Thus, it is the only deity that owes its origin to time, to history, as interpreted by Barboza, a Venus of this world, away from the pristinely mythic and zoomed through the archetypal constellation, to the life of men.

The nude, from the mistakenly called prehistoric "Venus" until the Western plastic is penetrated consubstantially by Christianity, it is the paradigm of the outer body it is a sure sign of the being in the nature in a spatial, historical and punctate mode, as a body among bodies, without establishing the radical ontological difference that exists between the conscious being and the entities shapers of the universe. Until the advent of the "inner man" Christian according to Roman Period and beginnings of the peak Middle Ages, the nude is the quintessence of a concept capable of understanding the man only as a specific unit limited in itself by its surface, in its purely external dimension, the Greek soma, in synthesis.

Everything is defined, bounded by a presentation of the human body, without the concerns of the infinite cosmic or the Augustinians inner depths of the soul .Neither in the fat females of the Upper Paleolithic, nor in the statues of classical antiquity- and not even in pre-Christian Hellenism art- there are approaches aimed at scrutinizing the psychological individual, but the generic as ideal type, and manifested in the very well-defined corporal extension.

When Miguel Angel answered the unpleased boorish by the distance between his works and the classical models, that between these and him, Christ mediated, he was at the heart of the difference: there is more spirit and inner revelation in Giotto's torso of The Last Judgment, in the Danae’s outstretched hand of Rembrandt, in the neck that Correggio painted in The Dream of Andromeda, or in the pelvis of Goya’s Nude Maja, than in any face of the Greco-Roman antiquity. After the beautiful and sensual psychological abundance even unknown to the busts of the Roman Empire.

With Diego Barboza, the flesh acquires intensity, as a matter subject to misery and sin but also to the role of externalizing a psyche, the richest and most fruitful of everything human. The anthropological conception of the artist before the female nude is like the appreciation of the personal psychic energy and of the corresponding characterizing features of the faces, for the eloquence of the corporal surface and, sometimes, of certain intimate blurriness of each figure .

Often, the category of artistic estrangement- so characteristic of post modernity-becomes with dialectics with the emotional approximation, making the absorption of the model in an ambiguous land, in a ground zero, where anything can happen.

If we observe the pastel painting The tedium, which usually is the self of the portrait has been fanned by the distance not from you but from her, that third person present in a relaxed and indifferent materialization without her being, however, hard and impermeable, pure physical object, through the subtleties of the line and tones that give the skin tremor within the static of the posture and extends to the humanized premises where the woman lies.

Her blank look of it is demonstrative sign of the insignificance into which has fallen the world of the female in boredom, it is the Nihilism of the environment, when everything becomes flat and the spirit is immersed in the one-dimensional. And take that look, in comparison with the body sitting on the furniture, in all evidence and fullness, absent of dynamism and psychic stimulus. Tedium possesses and rejects any hint of spiritual liveliness and interest- not even for herself- for the world.

She is only there to be painted. Otherness is an abyss of personal communication at such corporal consistency annoyed of the long hours of posing, when only the flesh remains as testimony, and, as Mallarme said, the flesh is sad. There is eroticism in The Story of Venus, despite these deformed bodies and the absence of slender sizes and the beautiful heat of youth. Eros is a god and a two faces concept, active and passive: tension of love and the stress of the one that is kind or loved. Or, in other words, erotic is the one who loves and also the object of making love. And several eroticisms appear in Barboza’s iconography through feminine archetypes. Ancient psycho-cosmic concentrations and constellations fixed in their images and their corresponding environments of situations, able to influence, along history, on the human beings, individually and collectively, according to the person and his times.

Aphrodite or Venus appears in Barboza’s imagery, sometimes in his mythical semantic solitude he brought to everyday history, but often contaminated by the archetype of Hecate, the terrible goddess of depths and night, with looks, as occurs in La Madame, capable of annihilating, in the past and present, the virtue of the unsuspecting and tempted man, eroticized by that erect female body, versed in tricks learned in a hard past of struggle with angry life.

Yes there is Eros, and none of these oils and pastels are less venus-erotic that works as well known as Venus at the mirror, Susanna and the Elders, and Susanna in the bath, by Rubens, or to find closer paragons, the woman lying in Leda and the Swan, by Michelena. On the other hand, that Barboza tries and finds the form and archetypal rhythm; it does not mean that he idealizes according to the naturalistic cannons. His fertile dependence with expressionism of Kokotschka frees him from such danger and such conventions. As a postmodern artist, Barboza participates in emphasis of interpretation that does not expect to focus on the beautiful and the pleasant, and thus the tracings of not a few modern painters of the female nude, such as Suzanne Valadon, Leon Bonhomme, Bonnard, Pascin , Marquet, Derain, without forgetting to mention a few icons of Matisse and Degas himself.

I have already mentioned like in some paintings, Venus appears with the contamination of Hecate, the dark and sinister part, man-eating, destructive and self-destructive, as in The Madame and in Stalking Woman, archetype both opposite and adjacent to Venus, but most of the time the presence of Aphrodite is autonomous, as in The Birth of Venus.

Here there is flesh in initial elasticity, of a woman who opens to the world and inaugurates it, proud of herself. She is about to get up from a sofa, in her birth into the environment of a premise where tectonics dominates and she gives herself an original meaning in that outbreak of the first movement and the tension towards the front of it. She is not born in the sea but in a room, in the contemporary sofa-bed. Something similar happens in the purity of Intimate Reflection, where Barboza’s lexicon permeates the whole surface and unfolds with amazement before this woman backwards whose unfathomable nature can only be apprehended with the help of the mirror, and that expands beyond the object-based limits, leaving men, the spectators, the game or the futility of establishing measures, divisions, coordinates, while she, the Venus woman, from her intimate world, nourishes the universe with her radiant dual presence: her back and the reflection, of that face that gives herself to us just in a moment, in a blink.

The body, sometimes, does not seem "the container of the soul" as the remains of it, in any case, lay scattered in bodily characteristics – according to the old saying that in man the soul is in the head, while in the woman it is throughout the body. The same happens with the large oil painting The Huntress, of excellent composition and better color, where the archetype of Venus stretches and gets ready to attract the prey, catch and devour it in the bonds of a love as intense as fleeting. It could have the Biblical legend, rescued by Baudelaire: quem quorem devoret, looking for someone to devour. This work reminds us that while Barboza masters the pastel, it is equally difficult with oil, using all its virtues, including glazes and textures.

Perhaps the most classic of the paintings in this exhibition would be The softness, where there in a kind of pleasant stupor lies Aphrodite enjoying only her body lying between reds and blues: pleasure of pleasures, of encouragement and above all of the matter, of the flesh, in a silent moment of life, in a precedent softness and delight of becoming. She is a woman in solace of her own anatomy.

With these and many other aesthetic charms, Diego Barboza gives us his gifts as a painter of race, his acting talent of art and his anthropological sense to the issue of nudity which, in our art history, had not been treated with so much quality after Reveron and Marcos Castillo.

Caracas, Venezuela

April, 1999

A theme, the flowers, it is just an excuse for Diego Barboza to get us closer to two important dimensions of his work. The first one refers to the act of painting...

A theme, the flowers, it is just an excuse for Diego Barboza to get us closer to two important dimensions of his work. The first one refers to the act of painting...

Diego Barboza- Traces of the imaginary

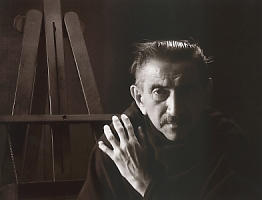

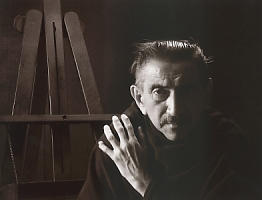

Diego Barboza has lived in harmony with himself. He has lived with his passions, his excesses, his sorrows and joys, sharing everything with his family, his dearest friends, and above all, with nature and the simple things that surround him. The most important thing is that as an artist he has been able to express all this in his artistic creation. The aesthetics of his works has depended on his ethic in life as a being and as an artist, thus following the most accurate principle of existence. The fundamental principle is that no concessions of any kind, without mislaying and without loud screeches, he has conducted his work and his life through a single and coherent way. His existence has been deeply tied to art and vice versa.

Producing a work rich in his changes, important in his contribution, sensitive in his artistic expression and broad in his proposals, this still young Venezuelan, and of the world artist, has led to a situation of mass communication, to use the same concept he gave to his visual expressions of the sixties and he defined as poetry of action. In this period of interest in conceptual art, not the object, he posed the performances he offered the ( from London and Caracas), apart from being carefully planned, they were “carefully combined”, color, shape, texture, to establish the relationship element-public- space that gives way to a work of collective communication. “Ephemeral manifestations of which documents have been printed valid for art history in Venezuela. (1)

From his beginnings, one of the characteristics of the Barboza’s work has been a distortion of the image. As a constant, this distortion is presented as the ideology that animates his work which is not perceived a non-conformist atmosphere, but a lawbreaking position of the human beings’ reality and his context. Barboza transgresses the traditional arts’ codes, being in control of any media he has chosen to express himself, whether drawing, performances, collage or painting itself. Besides this, another constant has been his “concern for man, life and the everyday. (2)

Life and Art

From the first and various meetings throughout our life, I have been close to Diego Barboza’s work. Some of these meetings took place around Plaza Morelos, in the sixties. Then in London in the seventies, and in Caracas in the eighties. Absences for a period and some brief reunions in the early nineties marked the resumption of an old friendship. For Diego’s friends are important both in their presence and in their absence. The present is a transition between the past and the future. It is the smallest portion of life. The present in Barboza’s work is a reminder of the past and a projection into the future.

Barboza began his career as a draftsman. Part of the history is the two drawings that lived in hiding with me. “Bikers against Agent 007 and the Rustler”, 1963. There can be seen some features present in the following pieces. If we fly from this date to the works performed by the artist today, it is clear the coherence of the plastic and stylistic process experienced throughout his career. From the beginning he was interested in figuration and by the distortion of the image, more and more pronounced in the inevitable process of continuity. Figuration and distortion have been two basic elements of his formal language. As an excellent and rigorous draftsman the sixties shows his prestige, as such continues today. The rigor with which he treats the line has made it to give in to his expressive purposes, to create a form that meets all the requirements of formal values. Here, the distortion of the shape is a plastic value, as posed, it is also an ideology, and in conclusion it is an artist’s personal decision to release his ghosts. After various forays into other media in the mid eighties he progressively goes into painting to, up to his current work, properly install himself in it.

Theme and Image

In presenting the catalog that accompanied a solo exhibition in 1996, the exhibits were defined by Diego Barboza as a continuation of his “arts creed…. without leaving behind the freedom that allows me to constantly encounter truths which represent my relationship with today and yesterday, as well as my vision of the future” (3) An unlimited continuity .

As any artist, he has used his own existential experience and his environment to recreate the images that make up his themes. But these have been images “not expressed in paintings of nostalgia for the irretrievable,-experiences of the past and of the elusive present- but an existing connection of iconography and strained relationships (sometimes obvious, sometimes hidden)… (4) They are images carrying a story transported by the spell demiurge creation, but not invented. The artist has structured them in arts context so that they exist as object and idea. An affectionate description allows the real object to express itself sensitively, avoiding narrative.

Diego Barboza thus manifests and expresses his subjective ability to evoke reality (objects and furnishings) in a pictorial context, as a phenomenon of a “baroque” plastic and existential sense the horror of emptiness becomes defining of his interpretation of the totality formed by different objects. The creative human space, specifically referred to the sensible experience of living the daily life of a table with various objects on top, of sticking to those seemingly insignificant things that have always accompanied him, the laborious study of the great masters of the universal art that thrill him, or the spiritual specialty of his street performances, defined by himself as “poetry of action” interact with the viewer’s space of contemplation.

Still Life Today

Still Life, or rather his essence, is the fundamental theme of the 1998 exhibit that Diego Barboza presents. The theme is not new, neither before nor now. But it is the treatment that the artist gives it as conceptual and formal as a result of the exploration of his own personal experience and art-historical research on the topic. Each of his still lives is an autobiographical fragment in several ways. Together they form a large personal landscape whose polysemic speech can be read and be perceived in several directions. One of them, for example, would be intimate, both in the personal sense and the everyday life of the artist as the viewer’s, another, the heroic sense of universal art and its masters, and another, a violation of the values of traditional painting.

They are the memories of inherited objects (the silver cup, the shoe when he was a year old, the base of the lamp when he was nine, the little things that are huge when inherited from the dead mother) they are the fixtures of his mythology of everyday life, such is the title of the exhibit (an apple of which only the core remains after being eaten, dishes, knives and forks, jugs, cups) which from being so real turn into a new objective and subjective space dimension, one of two situations that combine two perceptual situations, the reality of seeing the object and the one behind them, that for Barboza is “to portray what cannot be seen”. They are the possessions of his mythology of everyday life, repeated into obsessions.

He also uses objects that are outside the scope of his sentimental space. Those that attract him on the street, at the grocery store, the supermarket, in friend’s homes o when he is quietly sitting in the park, but they are not accepted at first sight as possible participants of the “feast”. An affective magic act must happen so they enter into his universe. Barboza states that to nurture his “imaginary” with other objects that are not mine, infatuation must be set in, I have to fall in love with them” (5). The artist needs the strength of the affective and emotional part in order to ideally conceive his iconography, which at the end he will present as a revelation. Barboza sentimentally tests the material in search of the form to express the motive of the painting.

The furnishings appear in Diego Barboza’s painting from the early nineties. In his 1992 works, one can see the presence of objects on a table, that with a thematic ambivalent meaning can be ready for before or after a meal, a good example is the canvas “After the Workshop”. From then on, he intensified his interest until he performed his last series of 1998.

Currently his guests of honor are the masters of history of universal painting that have painted still lives. Barboza with his pays them homage. Homage to Caravaggio is the rendition before the artist that first one known in history, specially invited to this workshop. The master of Aix-en-Provenze could not be absent, the great creator of beautiful still lives he pays his Homage to Cezanne, on whom he relies, especially in his proposal of broken perspective. Mentioning Cezanne we recall the words of Henry Brooks Adams “a master reaches eternity: one can never say when his influence stops”

In a visual paraphrasing, Barboza takes an art situation by using, for example, some elements that appear in the still lives of the “Guest Masters.” It is not a matter of paraphrasing a character or a sensible and affective art atmosphere but to solve the conceptual and formal problems posed from a personal exercise of intellectual reflection and the development of a personal art language. It happens then the complex process of deconstruction of the reality objects and their construction on the supporting surface, canvas or paper.

From his appropriations of Cezanne with his oranges, of Caravaggio with his apples or grapes, or Van Gogh with his sunflowers, one cannot talk about desecration, since they are intimate meditations performed from the heart; they are guided by love and a sense of beauty.

The Formal

The Series Beings and Mythology Furnishings of the Everyday Life (6) is composed by still lives that come from writings and drawings performed in the valued line, as mental and manual exercises done as dislocated photography, but in perspectives developed in digital art. In more prosaic terms, but maybe the most poetic ones, the object seem to be seen through convex or concave mirrors that can be found in amusement parks, this similarity is far more clear in the treatment of the human figure. In these notes is set the emotional relation between the artist and the individual and autonomous object. The objects likely to attract his attention, are first reconstructed in his workshop and then on the visual reality on the canvas or paper. The workshop, clean and tidy, that at times feels invaded by dishes with decomposing food scraps, by bitten fruits or half eaten, by vegetables or breads almost petrified, or by objects either dilapidated or in good condition. The food as another autobiographical aspect is an important part of the life of Diego Barboza. The Still life appears as the living model in the workshop and from it Barboza starts working the material, always from the inside out, ending up in the area by promoting the foreground. So the table is served with the paraphernalia that characterized the beginning or end of a meal, or still life with its surface covered by a table cloth full of oranges or other fruit. In the end the objects invade the audience space. His presence is undeniable.

The artist does not impose an artificial order in the configuration of the entire surface; he lets the items dictate and impose their ways according to the intrinsic qualities, exploring the structural possibilities of line and color. This way he produces images so strong that by analyzing them they stop being ideas that are subsequently expressed on the canvas. Barboza does not work with the memory only, or the chance. From the artistic point of view, the structure of the work has been calculated in advance. The strong linear arabesque of color and energy, have an impact on the viewer that allows you to appreciate the physical strength of the images, not being aggressive they contribute to exalt the feeling of tenderness that runs through the pictorial aspects of cubism, film , computer graphics, photography in motion come into play when analyzing the structure of the painting, whether oil or pastel, being necessary to add the baroque character summed up in the winding form and in constant movement. The paint layers overlap each other to structure a complex composition on which the artist maintains control. He knows exactly how to handle shapes and contours that are not scattered or clutter on the surface, thus articulating a sense of space and depth in motion.

The structure of the work starts from a perspective on planes, from the first inward; in inverse relation to the way the artist works it, who starts from the inside out. It's a perspective that is closer to Cezanne’s proto-Cubism, is meant as a movie idea that is broken. The objects are touched by a series of diagonals established by the direction in the straight lines imposed by forks, knives and other items that the artist presents with certain stiffness compared with the undulations of the other images, such as the profiles of chairs for example. These diagonals prevent the spreading of the images, solidified on the surface they inhabit. In his distortion of the images they set on the pictorial space with color and meaning in relation to each other as well as to the rhythm concretizing the composition of the pictorial field. The arrangement of objects, shapes creates a dynamic tension on the picture plane. The illusion of depth does not exist as an illusory representation but as an interaction of form and color. By solving the art problems in the foreground whose visual comes from below, the case of the pictorial space and emotional space in relation to time, Barboza solves it satisfactorily by the emotional component; he is concerned about "the relationship of space with the figure; that action, the trace, the Self, representing my very own feeling. I see the relationship between space-time as a feeling "(7)

Epilogue

For Barboza is more important the essence than the subject. Being among the objects the Being present in its absence. The past is the protagonist of this fact as in After Dinner or After Lunch. It is the exploration of feeling on the outside and inside of him and things. In 1988 he stated that for him art was a "continuous quest, a constant search within a reality that still gives me many opportunities" (8) Today and tomorrow, that reality still offers "multiple possibilities"

Bélgica Rodríguez

Caracas, February 1998

Notes:

1.- Catalogue of the Central Public Library "Dr. Julio Padrón "Maturin, s / f.

2.- A Conversation with Yasmin Monsalve. Caracas, August 1996.

3. - Catalogue of the exhibition at the Juan Ruiz Gallery. Maracaibo, June 1996.

4. - Carlos Silva. Catalogue of the exhibition at the Centre for European American Art. Caracas, September 1991.

5. - Conversation between DB and BR. 6. - Taken from a text by Carlos Silva.

7. - Interview with Moraima Guanipa. Daily El Globo, March 1993.

8. - Statements to the newspaper El Universal.

Born in Maracaibo, State of Zulia, Venezuela on February 1945. He died in Caracas on April 2003

Individual Exhibitions:

1963 Arts Center, Maracaibo, Venezuela

1964 Pez Dorado Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1965 Ateneo de Caracas, Venezuela

1967 Ateneo de Caracas, Venezuela

1970 The London Art News, Great Britain

1974 BANAP Gallery, Venezuela

1980 Gaudi Gallery, Maracaibo, Venezuela

1986 Arts Center, Maracaibo, Venezuela

1987 Euro African Art Center, Caracas, Venezuela

1990 Tito Salas Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1991 Banco de Maracaibo Hall, Maracaibo, Venezuela

1992 Ambrosinno Gallery, Coral Gables, USA

1993 Uno Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1994 Feliz Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1994 Namia Mondolfi Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1995 Odalys Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1996 Juan Ruiz Gallery, Maracaibo, Venezuela

1996 Modern Art Gallery, Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela

1997 Art National Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1998 Medicci Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

1999 Medicci Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

2000 Contemporary Art Museum, Maracay, Venezuela

2001 Contemporary Art Museum Zulia, Venezuela

2000 National Art Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

2001 Medicci Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela

Awards received:

1963 Stimulus Award - IX D’Empaire Hall, Maracaibo

1964 José Ortín Rodríguez Award- X D’Empaire Hall, Maracaibo

1965 Drawing First Prize - III Pez Dorado Hall, Caracas

1968 Enrique Otero Award V - XXIV Venezuelan Art Annual Hall

1973 Emilio Boggio Award - XXXI Arturo Michelena Art Hall, Valencia

1974 Antonio E. Monsanto Award - XXXII Arturo Michelena Art Hall

1985 Non Object Art Award - XLIII Arturo Michelena Art Hall

1986 Municipal Visual Arts Award – Municipal Council, Caracas.

1997 National Arts Award– CONAC

Represented by:

National Art Gallery, Caracas

Museum of Art, Caracas

Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas Sofía Imber, Caracas

Museum of Contemporary Art Zulia, Maracaibo

Museum of Contemporary Art Maracay Mario Abreu

Museum of Modern Art, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Museum of Graphic Arts, Maracaibo

Art Center , Maracaibo

Banco Central de Venezuela

Mendoza Hall, Caracas

CONAC, Caracas

Casa de Bolívar, La Habana, Cuba

Graphic Learning Center, Caracas

Universidad Simón Rodríguez, Caracas

BANAP, Caracas

Midland Group Gallery, London, GB

Municipal Council , Maracaibo

Municipal Council, Caracas

Municipal Art Gallery, Puerto La Cruz

Euro American Art Center Caracas

Interview with Mr. Tomás Kepets, director of the Medicci Gallery

Read more

"During those two decades, Galeria Medicci advanced into a river of creations and continues to show the majors artists, the vanguard of every moment, lucidity and everything that bridges with spiritual values. The experiences accumulated in more than two decades have sharpened the dynamics of today ". José Pulido

Works of renowned artists in the United States, the Caribbean and Latin America such as Manuel Mendive, Carlos Luna and the American sculptor Manuel Carbonell, as well as Venezuelan expats based in Paris, France, Annette Turrillo and Karim Borjas.